Xavien Howard's Abrupt Retirement: What the Stats, Contract, and Career Earnings Tell Us

In professional sports, as in financial markets, narratives are constructed to explain volatility. A team is a "Cinderella story," a stock is "poised for a breakout," an aging player "loses a step." These are tidy, digestible explanations for complex systems. But underneath the narrative, there is always the data. And the data rarely tells a tidy story. It tells a story of probabilities, regressions, and, often, inevitable declines.

The sudden retirement of Xavien Howard from the Indianapolis Colts is being framed as one of these narrative events. A veteran player, after a few rough weeks, deciding his family is more important than the game. It’s a respectable, understandable story. It is also an incomplete one. A more thorough analysis suggests this wasn't a sudden emotional decision, but the logical endpoint of a rapid, statistically observable collapse. The narrative provides the ‘why’; the numbers provided the ‘when’.

It began with a single, glaring data point: the Week 4 loss to the Los Angeles Rams. In that game, Howard, the 32-year-old two-time All-Pro cornerback, became a liability of the highest order. The Rams didn't just test him; they systematically targeted him as a structural weakness. Quarterback Matthew Stafford completed six of his nine passes thrown Howard’s way for 96 yards and a touchdown to Puka Nacua. The final box score shows Nacua with 13 receptions for 170 yards; a significant portion of that production was generated with Howard in coverage. When asked to assess his performance, Howard’s own summary was curt and accurate: “Not to my ability.”

One bad game can be an outlier, a statistical anomaly. Two bad games suggest a trend. Two weeks prior, against the Denver Broncos, the data was just as damning. Rookie quarterback Bo Nix was a perfect 7-of-7 for 75 yards and a touchdown when targeting Howard. In one sequence during that game, Howard was flagged three times in five plays (two for pass interference, one for holding), a cascade of errors that directly facilitated a Denver touchdown.

Compiling the data from just those two contests reveals a player whose performance had fallen off a cliff. Opposing quarterbacks targeting Howard had completed a combined 13 of 16 passes (an 81.25% completion rate) for 171 yards and two touchdowns. For the season, the passer rating against him was north of 120—to be more exact, 124.3. For context, the highest single-season passer rating in NFL history is 122.5. In effect, any quarterback targeting Xavien Howard in 2025 was performing at a level exceeding the best season any quarterback has ever had. This is not a slump. This is a systemic failure.

Decoding the Language of a Depreciating Asset

The Discrepancy Between Resume and Reality

The interesting part of this equation is observing the organizational response. Publicly, the Colts coaching staff deferred to Howard’s resume. Coach Shane Steichen noted he has “been a really good player in this league for a long time.” Defensive coordinator Lou Anarumo, who coached Howard in Miami, initially dismissed concerns about his age and the fact he didn't play at all last season. This is standard corporate procedure: praise the legacy of a depreciating asset while you evaluate its present value.

Yet, their language under pressure revealed the underlying conflict. When asked if he would reevaluate Howard’s starting role, Anarumo’s response was telling. “I think we will evaluate everybody every game,” he said. “Certainly, X is a player on the team, so he’s certainly going to get evaluated.” This is the kind of carefully worded statement that signals a problem. The follow-up was even more direct: “Rust or no rust, we’ve got to make sure we’re out there and we’re guarding the guys that we’re tasked to guard.” The subtext is clear: the excuses for poor performance have expired.

I've looked at hundreds of these situations in business and sports, and the pattern is remarkably consistent: when the performance data becomes indefensible, a new, more personal narrative is introduced to manage the departure. The Colts were facing a decision. The data indicated their emergency signing was no longer a viable solution. They could bench him, creating a media distraction, or release him, an unceremonious end for a player with a decorated past.

Howard’s retirement preempted that decision. It allowed him to control the exit.

The statement that his “kids are more important to me than football” is likely true. It is also strategically useful. It reframes a performance-based decision as a personal choice, preserving his legacy and avoiding the public indignity of being deemed no longer good enough. This is not cynical; it is rational. With significant career earnings (reported to be over $90 million), he had the financial security to walk away on his own terms rather than wait for the organization’s hand to be forced by the data. He saw the numbers, he understood the trajectory, and he made a calculated business decision about the future of his personal brand and well-being. The Colts needed a starting cornerback; what they had was a defensive liability whose past performance could no longer justify his present cost. The contract between player and team was broken long before the retirement announcement. The data simply made it official.

An Asset's Calculated Write-Off

This wasn't a choice between family and football. It was a textbook case of a veteran recognizing his performance arbitrage was gone. The on-field metrics had deteriorated to the point of no return. Rather than wait for the market—in this case, the Colts coaching staff—to execute a forced write-down by benching or cutting him, Howard initiated a voluntary liquidation of his career. He exited at a time and in a manner of his own choosing, a final, savvy move from a player who understood the numbers better than anyone.

Reference article source:

Related Articles

The AtomOne Fork: An Analysis of the Co-Founder Split, the Controversy, and What the Data Shows

A search for the term "AtomOne" presents a clean, almost perfect, case study in technological diverg...

A Presidential Pardon for Crypto's Pioneer: What This Means for Our Digital Future

The CZ Pardon Isn't Just About Crime—It's the Starting Gun for America's Next Tech Revolution When t...

EVAA Protocol: A Data-Driven Breakdown of its Core Metrics

The Illusion of Scarcity: Deconstructing the EVAA Protocol Surge The numbers on the screen are, by a...

That 700% BNB Attestation Service Pump: What Is It and Should You Even Care?

So, let me get this straight. There’s a token called BNB Attestation Service, or BAS, that went on a...

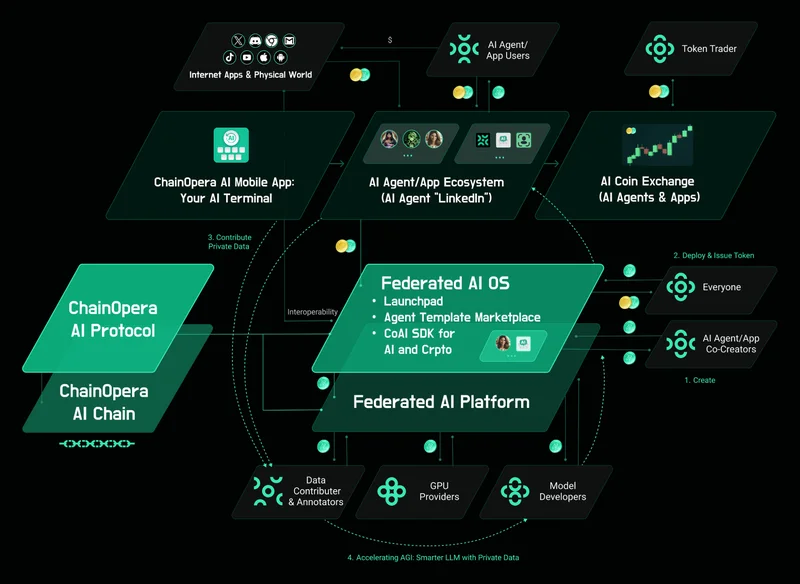

ChainOpera AI's 2,200% Surge: The Real Math Behind Its Explosive Growth and What Comes Next

The Anatomy of a Hype Cycle, or a Glimpse of the Future? There are moments in the market when an ass...

Zcash's Breakthrough: Why It's Surging and What the Community Thinks Is Next

I have to be honest with you. For the past few years, watching the Zcash (ZEC) chart has felt like w...